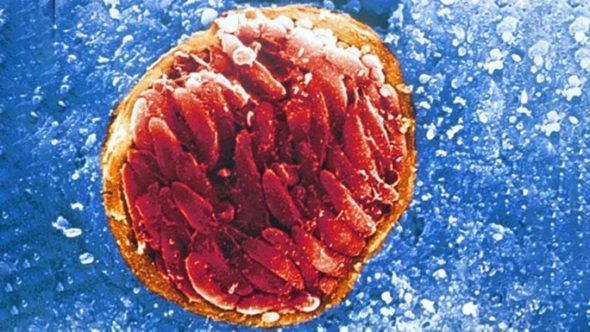

Toxoplasma gondii

Toxoplasma gondii is one of the world’s most prevalent parasites, infecting an estimated one third of the human population! Although it is only cats that can shed the infectious egg stage of the life cycle (oocysts) in their faeces, any warm-blooded animal can become infected with this parasite.

Livestock, such as cows, sheep, pigs and deer, can ingest Toxoplasma oocysts from pasture or feed contaminated with infected cat faeces and the parasite forms cysts in their tissues. People can then become infected if they eat a piece of meat containing a tissue cyst, which has not been cooked properly (e.g. rare steak, burger).

People can also become infected by ingesting oocysts in contaminated food and drinking water.

Most people who become infected with Toxoplasma have no symptoms at all or very mild flu-like symptoms. However, for people who have a weakened immune system due to illness (e.g. HIV) or immunosuppressive drugs (e.g. chemotherapy) the symptoms can be severe, causing eye disease, inflammation of the brain (encephalitis) or even death. Also, for pregnant women who become infected for the first time during pregnancy, toxoplasmosis can cause miscarriage, stillbirth or congenital defects.

Toxoplasmosis is also a significant problem for the sheep industry where the disease can lead to major economic losses for farmers. If a sheep gets infected for the first time during pregnancy, it can result in abortion, a mummified foetus, stillbirth or the birth of a live weakly lamb infected with the parasite. Once sheep have been infected with the parasite, they develop immunity and subsequent pregnancies should be protected.

Similar to infection in sheep, once people have been infected with the parasite, they are usually immune to re-infection. To avoid foodborne infection with Toxoplasma, cook meat thoroughly (or freeze it beforehand) and wash fruit and vegetables in water before eating. Toxoplasmosis is currently a notifiable disease in Scotland but not in the rest of the UK.

Toxoplasma is a very clever parasite and can change the behaviour of its hosts. Research has shown that rodents infected with Toxoplasma are less fearful of cats, making it more likely that they would be eaten in the wild allowing the parasite to complete its lifecycle. Studies in humans have suggested that people who have been infected with Toxoplasma are more likely to take risks and have road traffic accidents, and there is also a growing body of evidence linking Toxoplasma infection with neurological disorders such as schizophrenia. However, no direct link has been proven as yet.

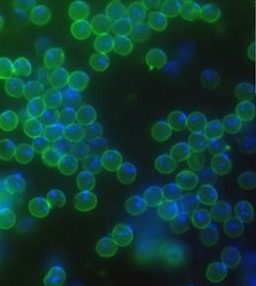

Cryptosporidium

Cryptosporidium parasites can infect many different animals including humans. People can become infected if they ingest parasite eggs (oocysts), causing a disease called cryptosporidiosis. Traditionally Cryptosporidium has not been thought of as a foodborne parasite but people can become infected if they consume contaminated food or drink.

The oocysts are not able to replicate outside the body but they are very environmentally stable and can stay infectious for many months. They are also resistant to common disinfectants at normal working dilutions, which makes them very difficult to kill.

Common symptoms of cryptosporidiosis include diarrhoea, vomiting, dehydration, nausea, stomach pain and cramps. In severe cases this can include profuse watery or bloody diarrhoea and in immuno-compromised people the infection can be fatal. Usually the infection is cleared once the infected individual mounts a protective immune response.

Humans can pick up the infection directly from animals or from water or other surfaces that have been contaminated. This is a particular problem during calving and lambing seasons, as one species of the parasite, Cryptosporidium parvum also infects livestock and is frequently produced in large numbers by neonatal calves and lambs. Another species, Cryptosporidium hominis, almost exclusively infects humans. Infection with this species in the UK has been linked to foreign travel, where people bring back the infection from abroad. It also has been linked to swimming pool outbreaks within the UK.

Drinking water or recreational water that has been contaminated with faecal matter containing oocysts is also a source of human infection. In the UK, tap water, supplied by the water industries, is monitored for Cryptosporidium and as a result, Cryptosporidium outbreaks related to drinking water are relatively rare and are often associated with private water supplies.

Contaminated water can be a potential source of infection during food and drink production and people can be infected by consuming contaminated fresh produce such as salad leaves, vegetables, fruit or milk. In recent years, in the UK, cryptosporidiosis outbreaks have been linked to ready-to-eat salad leaves, sandwiches containing salad, and unpasteurised milk. During food processing, water can also spread oocysts from contaminated produce across many products.

Another potential problem is contaminated water in the drinks industry. This is not thought to be a problem for the production of spirits as the high alcohol content kills the oocysts before they can be consumed but in non-alcoholic drinks and low-alcoholic drinks the parasite oocysts are likely to stay viable for long periods.

Good hygiene is the most important way to avoid Cryptosporidium infection. This means that fresh produce (leafy greens, vegetables, ready to eat salad and fruit) should be washed if they are to be consumed raw. The oocysts are also released from infected people in faeces and can infect other people if they are ingested. An infected individual can shed billions of oocysts and in humans as few as 10 oocysts can cause disease. Cryptosporidiosis in humans is a notifiable disease and infections are recorded and monitored to identify possible human outbreaks.

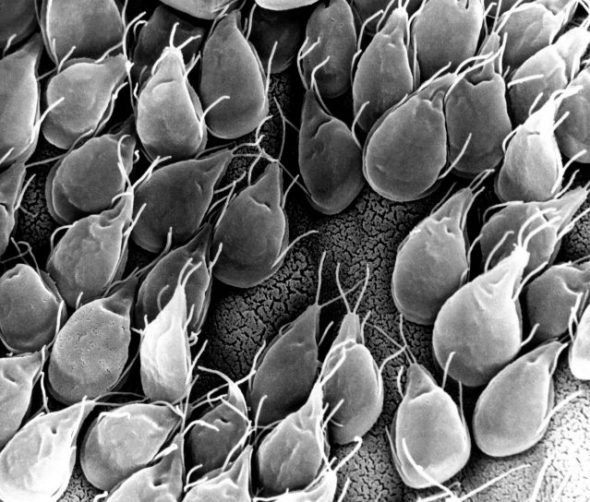

Giardia

Giardia can infect many different hosts but there is only one species that causes disease in humans and this can be called Giardia duodenalis, Giardia intestinalis or Giardia lamblia, as scientists have not yet agreed on what species name to use. This parasite can be transmitted from individual to individual in the form of eggs called cysts, which have a shell that protects the parasite from the environment. These cysts are not as strong as oocysts of Toxoplasma or Cryptosporidium and therefore are not as long lived and they are more sensitive to disinfection.

Infection occurs when a person ingests water or food containing faecal contamination with cysts that were produced by an infected individual or by direct faecal to oral transmission. The main transmission route for Giardia is thought to be human to human transmission but zoonotic (animal to human) transmission has also been suggested although the importance of this transmission route is not known.

Once a person becomes infected they usually develop diarrhoea, abdominal pain and foul smelling flatulence and belching. The disease is called giardiasis and can last for many weeks if untreated. The symptoms are caused by the parasite attaching itself to and feeding off the cells in the intestine of the infected person. This prevents nutrient and water uptake, which can lead to malnutrition and stunting of growth of the infected individual. There is evidence that some people will have prolonged digestive problems even after the parasite has been eliminated.

In Britain, Giardia infection has been linked traditionally to foreign travel, where people have picked up the infection in countries with poor sanitation or water quality. Recently it has been shown that transmission within Scotland was more common than previously thought when Giardia testing regimes for patients with diarrhoea in one health authority were broadened to include people with no foreign travel history. The study revealed that many people that tested positive for giardiasis had not been abroad and had acquired the infection in Scotland. This shows that giardiasis is underreported but it is still one of the most common causes of parasitic diarrhoea in Scotland with an average of 204 people being diagnosed with giardiasis each year. In addition many asymptomatic infections or people with only mild or short lived symptoms are unlikely to be detected.

Prevention of giardiasis is dependent on avoiding infection with the parasite, which means we rely on good quality water, sanitation and hygiene. In addition a better understanding of how people in Britain become infected will help to reduce transmission rates further. When the prevalence of giardiasis was analysed in Scotland it was noted that there are “age effects” and “gender effects”, which are probably due to poor personal hygiene. The study found that small children and young to middle aged men were more likely to be infected with Giardia. A possible explanation is that small children are more likely to put dirty hands or objects into their mouths and are less likely to wash hands. Studies have shown the latter is also true for young to middle aged men.

Read also

Farming and environment

Farm animal diseases

Animals, like humans can become infected with microbes and suffer from a wide variety of diseases.

Foodborne pathogens

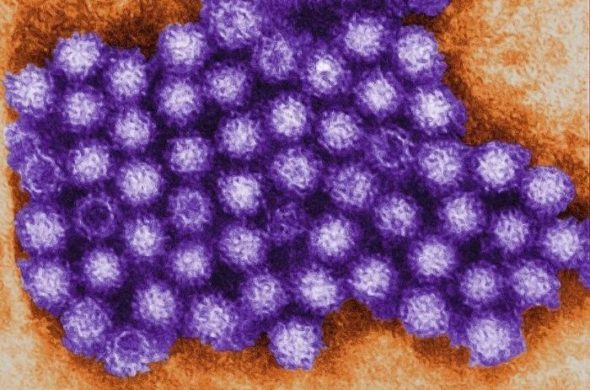

Foodborne viruses

18 % of UK food poisoning is thought to be caused by viruses. These viruses do not replicate in food but they are highly contagious.

Foodborne pathogens

How to reduce the risk

To lower the risk of infection and protect you and your family against infectious foodborne disease there are certain things you can do in your own kitchen.